Untitled Goose Retrospective

An agentic misadventure featuring light honking, heavy prompting, and questionable git etiquette.

Just like greatest goose-centered sandbox chaos simulator of all time, there’s a moment, mid-stream, where everything is chaos

You’ve got an AI agent that wants to help but doesn’t really know where the project is going. You’ve got too much boilerplate, too many half-baked ideas, and not enough clarity. The git history is muddy. The spec is fuzzy. You’re live on camera with two other hosts and hundreds of viewers. And it’s your turn to drive.

So what do you do?

You press the mic button, and you talk to the agent like it’s a colleague. Right in front of everyone. You tell it what you want. And for once, it listens. It resets the repo. It rewrites the files. It simplifies the scope. And suddenly, you’re back on track, with a playable RegEx learning game that’s shareable with the stream. Success! ✨

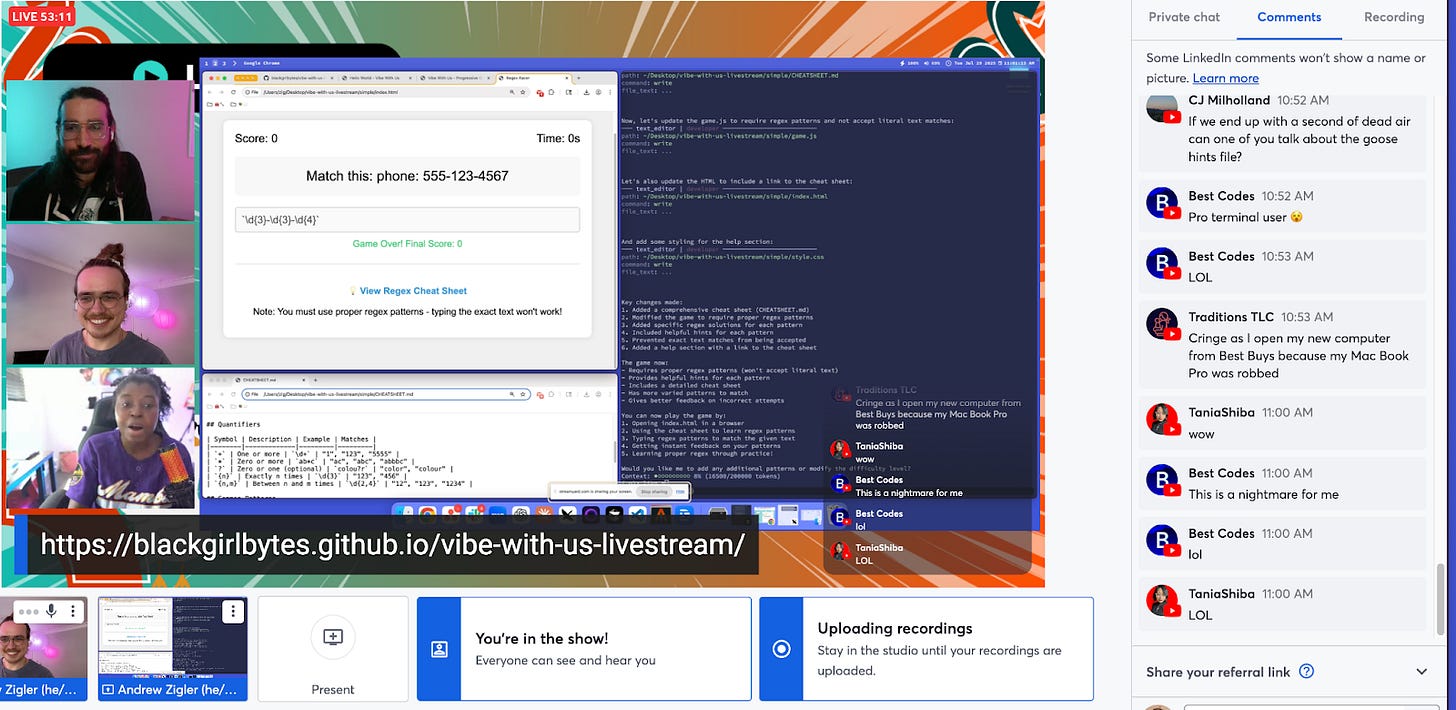

That’s what happened when I went live vibe coding with Rizel Scarlett and Jordan Bergero from Block. We were using Goose, an open source agent that Block is building, to explore what it means to code with LLM-native tools. We paired it with Claude and worked entirely out in the open: streaming our process, passing PRs back and forth, and letting the agents steer (when they could).

The result? A half-working game, a surprisingly profound set of lessons, and a new mental model for what agentic coding can actually look like in practice.

Let’s get into it.

What we built

The prompt was simple: build something live using Goose.

We started with a basic browser game shell. When it was my turn to drive, I pitched a RegEx learning game, something lightweight, interactive, and educational. But this wasn’t a private build session. We were live. And more importantly, we were collaborating through git, voice, AI prompts, and real-time PR swaps.

This meant friction.

By the time the project hit my lap, the repo was bloated. Our LLMs had been overzealous. The scope had spiraled. It wasn’t clear where we were going, or how to get there before the stream ended.

This is the moment most developers know well: too much mess, not enough time.

That’s when I hit voice-to-text.

Voice as interface

There’s something magical about speaking to an agent when your brain is overloaded. Instead of fighting with the keyboard, I gave the AI a direct, contextual prompt. I told it to simplify the game. Strip it down. Make it work.

And it did.

It took the repo, restaged the files, and gave us something playable by the end of the stream. It wasn’t perfect, but it was clean. Focused. Something we could show.

This moment felt like a shift.

I wasn’t just prompting an AI. I was collaborating with intent, with constraint, with a clear context. And by using voice, I removed all the friction of syntax and formatting. It was raw idea-to-implementation, without the ceremony.

Even Angie Jones called it out during the stream (and my inner fanboy was for sure screaming)! It wasn’t just a cool trick. It was a live demo of how removing friction is what counts when working with agents.

Lessons in context engineering

Here’s what I’ve learned about building agentically (especially in public) with tools like Goose:

Start with the spec

Don’t dive into code. Don’t even start with a prompt. Start with context.

Ask:

What are we building?

What’s the user flow?

What are the constraints?

What are the rules?

Then write that down. In Markdown. In code comments. In README files. You’re not just documenting for humans, you’re feeding your agent.

The clearer your input, the better your output. Think of it as context engineering. You’re building scaffolding for the AI to reason inside of.

Inputs > Outputs

This isn’t prompt tweaking. It’s architectural.

You want to spend your time shaping the setup:

Pull context from git history

Define workflows in natural language

Use evals, tests, and scripts to steer the agent

Remember: chats are ephemeral. If you’re not capturing your decisions, you’re going to repeat them. And your agent won’t remember them either.

Use the AI to improve the AI

Let your tools teach themselves:

• Use agents to write tests for their own code

• Ask for simpler prompts, then reuse them

• Build smaller modules so your agent doesn’t get lost

And if things go sideways (which they will), fork the world. Make a branch. Hide out in a subfolder. Shrink your scope. Reduce uncertainty until you can regain control.

Good agents aren’t magic, they’re modular. They do best in clearly bounded environments. Your job is to shape that environment.

Language matters

Working with JavaScript on stream reminded me how languages like Rust or Go are great for agentic dev because of their strong typing and compile-time checks. They give the AI feedback loops. They enforce boundaries.

This isn’t a language war. But if you want to build with agents, pick ecosystems that give you good errors. TypeScript. Rust. Go. Python with type hints. These make your agent smarter, not just faster.

It’s hard to build in the open

Let’s be real: live coding is scary. Live coding with AI? Even more so.

You’re showing your thinking in real time. You’re debugging while explaining. You’re making design calls with 200 silent watchers and an agent that doesn’t always listen.

But here’s the twist: the agent reduces the anxiety.

I’ve done live coding for years. Back then, it was just me and my IDE. If I blanked, I blanked. Now? I’ve got a collaborator. A second brain. A fallback. Even when I’m stuck, I can describe what I want and the agent helps me try something.

That shift is huge.

It turns the performance into a conversation. It makes building in the open less about perfection and more about exploration. That’s the vibe. That’s the point.

From vibe to practice

This wasn’t just a stream. It was a rehearsal for the future of software development.

A future where:

Git is the whiteboard

The agent and their subagents are your entire team

Markdown is your spec

Voice is your interface

And vibe coding is a methodology

We’re in the early days of this shift. Tools like Goose are opening the door. Platforms like Claude are enabling context-rich sessions. And practitioners, like my friends Rizel and Jordan, are showing us what’s possible.

The rest is up to us.