The hidden complexity of robot networks

Why robotics’ hard-won lessons on real-time AI matter for every engineering leader

A guest article by David Chen, GM of Robotics at LiveKit.

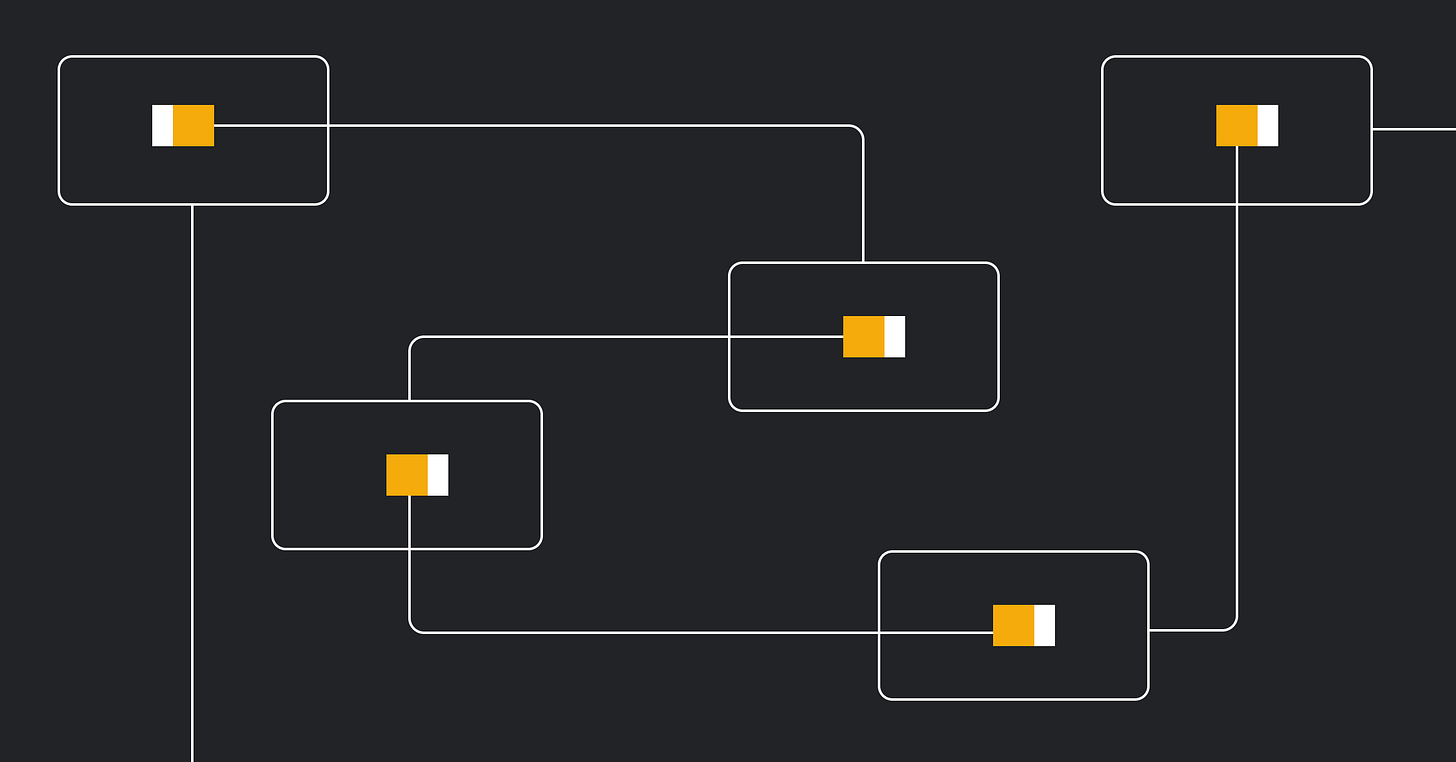

Most people assume a robot’s intelligence lives on the machine itself. It doesn’t have to. We’re heading toward a hybrid edge/cloud architecture for robot intelligence, and the evolution of physical AI is forcing robotics companies to solve networking problems that software leaders will eventually face too.

The pattern mirrors how LLMs evolved. Today’s LLMs split between small models running locally for simple tasks and massive proprietary models accessed through cloud APIs for complex reasoning. Foundation models being developed for robotics—vision-language-action models and similar approaches—will likely follow the same path.

In this architecture, the robot’s brain may exist primarily in the cloud, fine-tuned for specific tasks like cleaning a kitchen or sorting objects in a warehouse. The physical robot connects the real world to cloud-based intelligence through its sensors: vision, touch, and whatever other modalities the task requires.

This raises new demands for network infrastructure. The perception-to-decision-to-action loop needs to happen rapidly. A robot responding to its environment can’t wait for a round trip to the cloud if that adds hundreds of milliseconds to its reaction time.

After spending a decade building autonomous systems—first drones scanning construction sites and mines, then autonomous tractors navigating vineyards and orchards—I’ve learned that this split between edge and cloud intelligence already works in production today, but only when you solve specific networking challenges. The difference is that today’s “cloud brain” is a human operator. Tomorrow’s will be an AI model. Either way, the engineering problems are the same.

When milliseconds really matter

Companies deploying autonomous vehicles are supplementing AI with human operators, because realistically edge cases still require human judgment. The AI handles the routine 80%, while humans step in for the complex 20%. But this hybrid approach only works if the network can support real-time human intervention.

Consider a 40-ton excavator operating in a remote mine in Brazil. An operator monitoring the vehicle from a command center spots an obstacle and needs to issue an emergency stop. Every millisecond of delay between the operator’s command and the vehicle’s response matters. Human reaction time hovers around 200 milliseconds. If your network infrastructure adds another 300 milliseconds on top of that, you’ve effectively doubled the stopping distance. In robotics, just a hundred extra milliseconds could result in a serious injury, or worse.

This latency requirement affects teleoperation across the robotics industry. But here’s what makes it an engineering problem rather than a simple bandwidth problem: you need sub-200 millisecond latency while handling fluctuating network conditions. An autonomous tractor in a vineyard doesn’t have fiber connectivity. A mining vehicle in a remote location relies on private cellular backhaul.

Real-time robotics requires different network protocols than traditional web applications. Most software development operates on comfortable assumptions: Web applications can buffer. Mobile apps can retry. A 500ms delay might annoy a user, but it won’t cause catastrophe. Robotics changes these assumptions entirely.

Protocols built for robotics need to adapt bitrates to network conditions in real time, handle packet loss gracefully, and maintain quality when bandwidth fluctuates. When the network degrades, you can’t just show a loading spinner. You need to reduce video quality on the fly, drop non-critical sensor streams, and keep the command channel open at all costs.

The same latency requirements that matter for teleoperation will matter even more when the robot’s decision-making happens in the cloud. The challenge for robotics companies becomes: which intelligence lives on the edge, and which lives in the cloud? Simple reactive behaviors (obstacle avoidance, basic motor control, etc.) probably stay local. Complex reasoning about unfamiliar situations or fine-grained manipulation tasks might need the full power of cloud-based models. But that split only works if your network can handle the back-and-forth reliably.

Multiple sensors, multiplied problems

Web and mobile applications typically deal with a single data source: a user’s browser or phone. One camera, one microphone, one stream of input.

Robots operate differently. A vehicle might have a dozen cameras, each streaming high-resolution video simultaneously. LiDAR sensors generate point clouds. Radar tracks moving objects. GPS and IMU sensors provide positioning data at hundreds of hertz. All of these need to stream to the cloud and out to monitoring systems continuously.

This creates a scaling challenge that traditional infrastructure wasn’t built to handle. Each client in a standard video conferencing setup connects to a handful of other clients. In robotics, you might have twelve camera streams from one robot, all needing to reach multiple operators in a command center. The bandwidth requirements multiply quickly.

The problem compounds outside laboratory environments. Traditional approaches to video streaming break down when they assume stable, high-bandwidth connections.

What robotics companies build differently

Most robotics companies build two separate systems: a real-time piece for monitoring and teleoperation, and a separate piece for capturing and storing data. The real-time component might start out as simple peer to peer services, but then will need to be replaced as the number of operators grows. The storage piece becomes unmanageable as soon as you start generating terabytes of data at scale.

You can’t just transport the data and forget about it. You need to capture, store, and replay massive volumes of sensor data. If a robot causes an accident, you need logs to understand what happened. If a teleoperator makes an error, you need to review their commands alongside the robot’s sensor data. If you want to train AI models to handle the edge cases humans currently manage, you need thousands of hours of teleoperation data showing how humans solve complex situations.

A single autonomous vehicle generating video from twelve cameras, plus LiDAR point clouds, plus telemetry data, can produce terabytes per day. Multiply that by a fleet of robots, and you’re quickly dealing with petabytes.

Why software leaders should care

Robotics exposes challenges that the web and mobile worlds never had to solve—the difference between success and failure is measured in milliseconds. As physical AI evolves toward hybrid architectures, these challenges intensify. The robots of the future may look like thin clients, but the infrastructure connecting them to cloud-based intelligence will need to be anything but simple.

The teams tackling these problems with a sharp focus on real-world applications, not just lab demos, will uncover hidden complexities, drive new kinds of engineering, and change the way robots operate across industries—from autonomous vehicles and mining equipment to agriculture.