Mise en place for agentic coding

Deliberate preparation is the missing discipline in agentic development

In professional kitchens, there is a practice called mise en place, a French term meaning “everything in its place.” Before a single flame is lit, before any oil hits a pan, the chef arranges every ingredient, every tool, every vessel in precise order. Onions diced. Sauces portioned. Knives laid out. The preparation is so thorough that once cooking begins, the chef’s hands never pause to search for anything.

To an outsider watching through the kitchen window, the preparation phase looks like nothing is happening. The chef isn’t cooking. They’re just... organizing. Arranging little bowls. Reading the ticket. Thinking.

Then service starts, and what follows looks like magic: dozens of dishes flowing out in perfect sequence, each one composed from ingredients that were ready before the first order came in. The speed of service is a direct function of the stillness that preceded it.

I’ve been thinking about this concept a lot lately, because I believe it describes something important about the way agentic coding actually works, when it works well. And I recently had an experience that crystallized the idea in a way I want to share.

The preparation problem

There is an emerging consensus in the AI-assisted development community that the primary bottleneck in agentic coding is not code generation. Models are remarkably good at writing code. They’re fast, they understand frameworks, they can scaffold entire applications in minutes.

The bottleneck is alignment.

When an agent writes code that doesn’t match what you intended (i.e., when it makes an architectural choice you disagree with, or implements a feature in a way that misses the point) the resulting debugging and refactoring cycle can consume 70% or more of your total development time. This is a widely observed pattern.

Geoffrey Huntley has discussed it in the context of the Ralph Loop. Steve Yegge has built entire orchestration systems like Gas Town around the premise that agents need rich, persistent context to perform well. Jeffrey Emanuel's work porting Yegge’s beads to a lightweight Rust binary (my personal agentic task manager of choice) reflects the same insight: agents need structure, not just prompts. Even my most recent conversation with Dex Horthy rang true with the same takeaways.

What all of these practitioners have converged on, independently, is something that resembles mise en place. The idea that the work you do before the agent writes code — the context you create, the constraints you define, the task decomposition you perform — determines the quality of everything that follows.

This is not a new insight in other disciplines. In education, it’s called backward design when you start with what the student should understand, then design the assessment, then design the instruction. The lesson plan comes before the teaching. In architecture, it’s the programming phase where you define the functional requirements of a building before any sketching begins. In military planning, Eisenhower’s observation applies:

“Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”

In agentic coding, the equivalent practice doesn’t have a name yet. So I’m going to call it what it is: mise en place.

A recent case study

I want to describe an experience I had recently, not because the outcome was remarkable (though it turned out well), but because the process illustrates this principle clearly.

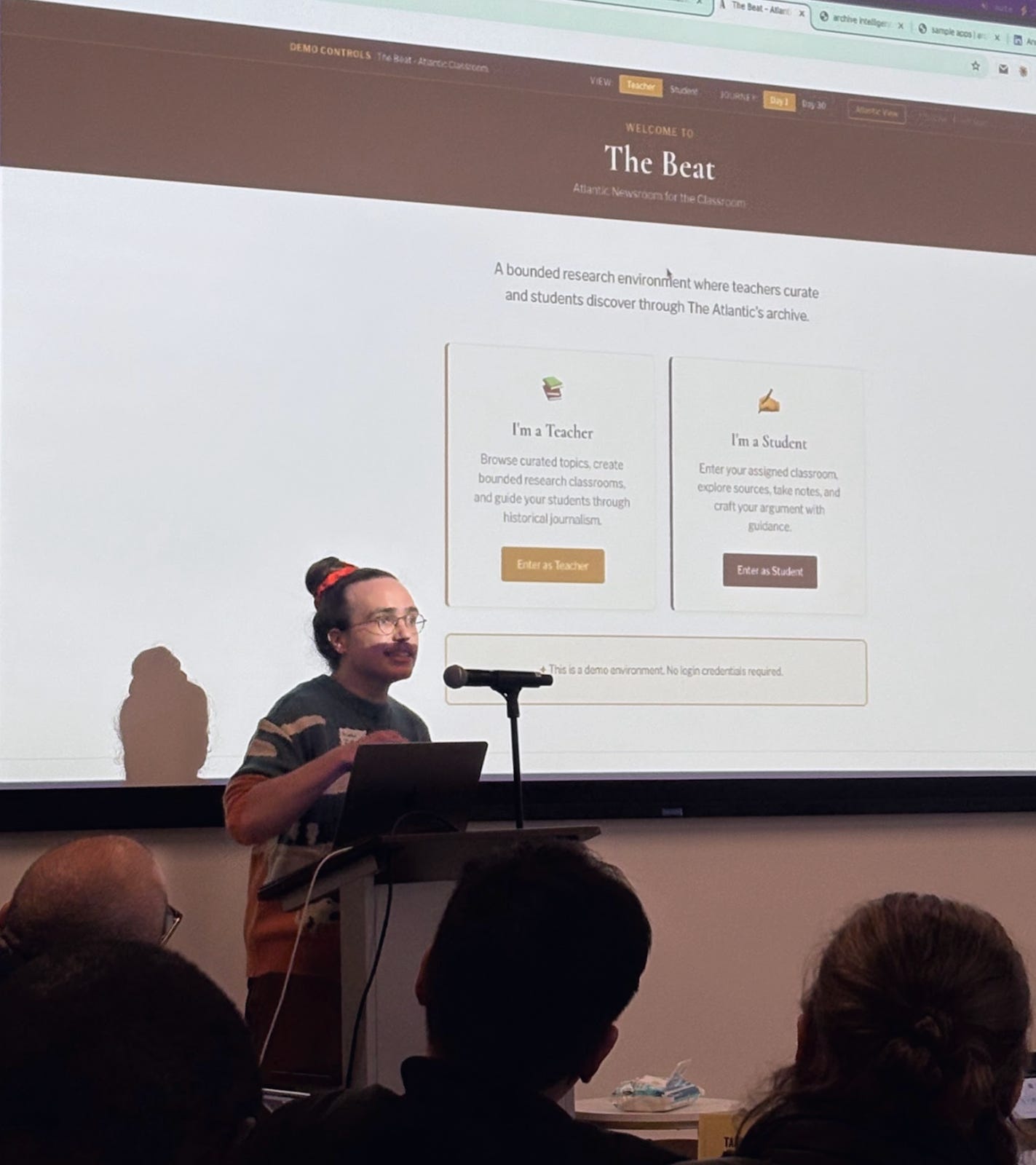

In late January, I participated in a hackathon co-hosted by The Atlantic, Infactory, and Hacks/Hackers. The challenge was to build “trusted news experiences of tomorrow” using The Atlantic’s archive and Infactory’s AI-powered API. There were about a dozen teams, a 5-hour build window, and a panel of judges that included Nicholas Thompson, CEO of The Atlantic.

The teams around me were building interesting things like knowledge graphs, content recommendation engines, infinite canvas article explorers, AI-generated timelines. Good ideas, technically ambitious, and most teams started coding within the first 15 minutes.

I didn’t write any code for the first 2 hours. Instead, I was chatting with my computer.

This was not procrastination. It was mise en place.

What preparation looked like in practice

The Atlantic’s product team had published a set of challenge prompts for the hackathon. One of them asked:

“How might we make The Atlantic accessible to high school and college students and teachers?”

I have a background in education (I taught elementary and middle school before moving into engineering) so that prompt connected two parts of my experience that don’t usually overlap. The connection produced a specific product idea: a platform where teachers curate bounded research environments from The Atlantic’s archive, and students conduct research within those boundaries using a Socratic AI tutor that only asks questions, never provides answers.

The product idea was clear to me almost immediately. But having an idea is not the same as having the context an agent needs to build it. So I spent the first 2 hours creating that context, deliberately, using a process I’ll break down.

Phase 1: Contextual grounding

I use Wispr Flow for voice-to-text dictation, which means I work by talking rather than typing. This is a meaningful distinction. When you type, you tend to self-edit in real time, producing tighter but narrower output. When you speak, you think associatively and make connections, follow tangents, circle back. The transcription captures the full texture of your thinking, including the false starts and course corrections that turn out to be valuable later.

In the first phase, I dictated a series of markdown documents that together formed a “briefing packet” for Claude. These included:

The hackathon event description, converted to Markdown

The Atlantic’s product team challenge prompts

A transcript of Nicholas Thompson’s interview in The Verge about The Atlantic’s AI strategy (this gave Claude context on the institution’s concerns about content authenticity, “enshittification,” and the subscription business model)

Notes on what other teams were building, for competitive differentiation

A long, unstructured conversation about my teaching experience: what it feels like to design a learning environment, why productive struggle matters pedagogically, how a good teacher creates conditions for thinking rather than delivering answers

That last document took the longest to produce. It was essentially 20 minutes of me rambling about education: the felt experience of standing in front of a classroom and trying to create the conditions where students have to actually think.

This is the kind of context that agents cannot generate for themselves. It is domain expertise, lived experience, and value judgments. That’s an irreducible human contribution that no amount of prompt engineering can replace. But once it’s captured in a document that the agent can read, it becomes the foundation for everything that follows.

Phase 2: Collaborative specification

With the contextual grounding in place, the second phase involved working with Claude to produce a detailed product specification. This was a genuinely collaborative process where I would describe what I wanted, Claude would propose implementation details, and I would accept, reject, or modify its suggestions based on my understanding of the problem space.

Some of the disagreements were instructive:

Claude proposed supporting multiple assignment types. I constrained it to one, because the demo was three minutes long and I wanted one thing that worked beautifully rather than three things that worked adequately.

Claude suggested using mock data for development speed. I insisted on real API data, because the judges would recognize the difference between a product built on real journalism and one built on placeholder text (and using the API was the whole reason we were there).

Claude wanted to build a comprehensive analytics dashboard. I scoped it down to the minimum needed to demonstrate that a teacher could see the student’s research journey, not just their final submission, because the journey is the pedagogical point.

Each of these decisions reflects a value judgment that only I could make, informed by my understanding of teaching, of the hackathon context, and of what would resonate with the judges. The specification that emerged from this phase was detailed enough that any developer (human or artificial) could implement it without asking clarifying questions.

Phase 3: Task decomposition

The final preparatory step was converting the specification into a structured task system. I used the aforementioned beads_rust for this. Beads are just structured JSON task records with priorities, dependencies, and acceptance criteria. They function as the coordination layer between a human orchestrator and multiple parallel agents.

I launched an orchestrator agent that read the complete specification and produced 42 beads, one for each discrete unit of work. Every screen, every feature, every integration point was decomposed into a task with clear boundaries and success criteria.

At this point, 2 hours had elapsed. I had produced:

A contextual briefing packet (5-6 markdown documents)

A detailed product specification (every screen, interaction, and data flow)

A structured task breakdown (42 beads with dependencies)

Oh, and 0 lines of application code 😇

What happened when the agents started

When I finally launched the implementation agents, the results were striking in their speed.

I deployed four subagents in parallel, each responsible for a distinct feature:

Classroom creation flow: teacher selects topic, curates articles, generates class code

Student join flow: enter code, access bounded research workspace

Day 1 / Day 30 demo toggle: show empty workspace vs. research in progress

Socratic AI tutor: question-only assistant with pause detection and milestone triggers

I didn’t give them any kind of fancy roles (don’t give into the temptation to play house with your agents, you don’t need a bunch of distinct skillsets). All four completed within approximately five minutes. Just like that, the core application scaffolding was functional.

I want to be precise about what “functional” means here. The agents produced the correct architecture with components in the right places, state flowing in the right direction, and routing working as specified.

Of course, there were bugs. There were styling concerns. The API integration needed debugging. Article content was being truncated in some weird ways.

But the fundamental shape of the product was right, because the specification was right. The agents didn’t have to make architectural decisions or guess at my intentions. They executed against a clear, comprehensive plan.

The remaining hour was spent on testing, bug fixing, and deployment with a very casual pace. I would identify an issue while prepping the demo flow, create a bead for it, and dispatch a subagent to fix it. At the speed of roughly one issue every 3-4 minutes.

The final product (called The Beat) included teacher dashboards, student research workspaces, article highlighting and annotation tools, citation validation, a rich text essay editor, and a Socratic AI tutor that asks genuinely challenging questions without ever providing answers.

The judges selected it for first place.

What I think this illustrates

I’ve been reluctant to frame this experience as a personal achievement, because I don’t think the interesting part is that I won a hackathon. The interesting part is why the approach worked, and what it might suggest about the direction agentic development is heading.

The core observation is simple: deliberate preparation compresses implementation time.

The two hours I spent not-coding were not wasted time. They were the mise en place that made a near-one-shot implementation possible. The agents performed well not because they’re magic, but because they had rich context, clear specifications, and well-defined task boundaries.

This is a counterintuitive allocation of time in a hackathon setting, where the dominant strategy is to start coding immediately and iterate. But iteration is expensive when your agents are generating code that doesn’t match your intent. Every misaligned component creates a debugging cascade. Every architectural disagreement requires refactoring. The “start fast and iterate” approach optimizes for the feeling of progress, not for actual progress.

The mise en place approach optimizes for alignment, and treats implementation as the final, fastest phase of a process that began much earlier.

The toolkit, deliberately simple

People have asked about my development environment, and I think the simplicity is itself part of the point.

I work in a terminal over SSH. No IDE, no graphical interface, no agent dashboard. Claude Code as the primary agent runtime. Wispr Flow for voice-to-text dictation. Beads for task decomposition and tracking. Bun, Rust, Python… all standard langs, nothing exotic.

There is a temptation right now to use AI as a justification for adding complexity, to layer on more abstractions, more orchestration layers, more frameworks between you and the problem.

I think this is a mistake.

The value of AI in a development workflow is that it lets you work closer to the material, not further from it. You want to reduce the distance between your thinking and the code, not increase it.

Geoffrey Huntley describes this as the Ralph Loop. The practice of breaking problems into the smallest possible units so that agents can iterate on them with minimal ambiguity. The principle is reductive, not additive. You remove layers. You simplify interfaces. You create clarity.

The same principle applies to the toolchain itself. A terminal and a voice interface is a remarkably direct way to work. There is almost nothing between my thinking and the agent’s execution. The friction that remains is the useful friction — the time I spend thinking about what to build and why, which is exactly the friction that produces good outcomes.

Context fluency as a practice

There is a phrase I keep returning to: context fluency. It describes the emerging skill of creating rich, structured context that agents can act on by capturing domain expertise, value judgments, and design intent in a form that’s legible to an AI system.

This is a different skill from code fluency, though it builds on some of the same foundations. It involves:

Decomposition: breaking a problem into discrete, parallelizable tasks with clear boundaries

Specification: describing not just what to build but why, so that agents can make aligned decisions at the micro level

Constraint definition: knowing what to exclude, what to simplify, what to defer is a first-class concern

Domain encoding: capturing the lived experience, value judgments, and tacit knowledge that agents cannot generate independently

I find it interesting that this skill set maps closely onto what good teachers do. A well-designed lesson plan is an exercise in context fluency. You’re creating conditions where the learner (whether student or agent) can do meaningful work independently, because you’ve done the hard work of structuring the environment in advance.

I used to prep lesson plans for students. Now I prep lesson plans for agents. The pedagogical instinct is the same. You figure out what the learner needs to know, you structure the information so they can act on it without constant supervision, and then you step back and let the work happen.

An invitation to practice

I want to close with something I’ve been saying to people who ask about this workflow: the barrier to entry is lower than it appears.

The tools are available. Agentic task management tools like beads are open source. Claude Code is accessible. Voice-to-text dictation is a solved problem. The development environment I described (a terminal over SSH) is the simplest possible setup. Tmux is a 20-year-old technology!

What’s harder, and what I think is worth practicing, is the discipline of preparation itself. The willingness to spend time thinking before building. The patience to create context documents when you could be writing code. The confidence to sit in a room full of people who are already coding and choose to keep talking to your computer instead.

This is not a natural instinct for most engineers. We are trained to value output: lines of code, commits, shipped features. Sitting quietly and dictating a markdown document about your domain expertise does not feel like engineering. It feels like procrastination.

But I think the evidence is starting to suggest otherwise. And I think the developers who learn to practice mise en place are going to find themselves building things that are more aligned, more coherent, and more reflective of their actual expertise than anything they could produce by starting fast and iterating.

The code is the easy part. It always was, even before AI. The hard part is knowing what to build and why. And that work — the quiet, unglamorous, deeply human work of thinking clearly about a problem — is still very much a job for us.

Great post!